MY GLIAL CELLS 2.

A Rather

Adventurous Endeavor

My second foray into the world of science was much more daring, and difficult than the past. When I was reading psychology papers, I often noticed that it was hard to prove that a phenomenon had scientific origins, aside from being emotionally-based. What I mean by this puzzling statement, is that while DSM-5 conditions have a clear point of origin, emotion driven social interactions are often hard to pinpoint.

.png)

ABSTRACT

The avoidant attachment style, when it was first proposed, analyzed the various responses in infants in response to the sudden absence and return of a primary caretaker [1]. Usually, individuals start to develop avoidant attachment styles depending on their relationship with their primary caretaker. As such, to properly understand avoidant attachment styles, it is imperative to understand where they stem from. Here, we propose a systematic analysis regarding the avoidant attachment style. This manuscript will explore the origin of the avoidant attachment style, how different avoidant attachment styles manifest according to their conditions, and finish with a review of various neurobiological factors which influence individuals with the avoidant attachment style. We aim to summarize various aspects of the avoidant attachment style and suggest how individuals with such an avoidant attachment style may proceed on their healing journey.

I. INTRODUCTION

Attachment theory was first mentioned by John Bowlby when he was studying the various circumstances that led infants and young children to show specific reactions depending on their upbringing [1]. Concurrently, Ainsworth et al., conducted a study divided children and their attention styles on how the children interacted with their caregivers or people special to them [2]. The first, the secure attachment style, was characterized as showing resilience and patience in moments of adversity and uncertainty. The anxious attachment style, on the other hand, was quick to cry or panic in the absence of their caretaker’s presence. From a psychological perspective, anxious attachment is shown in children who display an upregulation of their emotions; that is, they show tendencies to gravitate toward emotions that elicited a response, and if they did not receive one, they then increased the magnitude of their emotions. For example, a child will start initially crying, but upon no response from a guardian figure, will start to cry louder and add physical interactions with the surroundings, such as slamming their foot or throwing objects. The avoidant attachment style, on the other hand, showed characteristics that were the complete opposite of anxious attachment style.

The avoidant attachment style is often characterized by disengagement from the source of conflict, which is often the caregiver [3, 4]. The way this manifests is shown in limited or no interaction with the caregiver. An explanation of why the child adapts this particular attachment style is reflected by how the caregiver interacted with the child. If the child was shown emotional neglect or if his or her emotional needs were downplayed, the child may perceive the caretaker as an identity who will eventually betray the child. Consistent neglect of the child’s wants or needs, especially if they continue toward adolescence, will lead to the child showing hyper-independence characteristics, a reflection of a betrayal wound [5].

While the initial studies regarding attachment styles focused on children, these behavioral studies also shed light on some confusing behavior that adolescents and adults showed in their lives. The abandonment of a perfectly good relationship due to extreme uncertainty of the future, the sudden loss of feeling for a specific other, and, in some cases, a rewriting of past events as a maladaptive protection strategy were some symptoms that were shown in adults with avoidant attachment tendencies. More often than not, it is the partner of avoidant individuals who suffer from a sudden rug pull of a situation, especially since a sudden discard is characteristic of avoidant individuals in a relationship. Indeed, the emotional distress is significant enough to cause individuals who have a secure attachment style to suddenly display anxious attachment tendencies; a trauma wound of sorts from the betrayal of a loved one. It is here, it must be said that this manuscript is not an attack on individuals with avoidant attachment styles, but rather a study into the origins of the maladaptive style, its characteristics in adult romantic relationships, its neurobiological characteristics, and how avoidant individuals can learn healthy emotional regulation methods.

II. METHODOLOGY

An initial literature search was carried out on PubMed (National Library of Medicine) and Google Scholar to research studies regarding the various aspects of avoidant attachment. Search terms included “avoidant attachment” maladaptive avoidant attachment,” “ avoidant attachment origin,” and “neurobiology and avoidant attachment,” combined with Boolean operators (AND, OR) to maximize retrieval of relevant studies. The search strategy was designed to investigate both the psychological and neurobiological actions of avoidant individuals. Follow-up research search, which focused on healing the avoidant attachment style, included the “emotional regulation of avoidant attachment” and “avoidant attachment and therapy.”

All retrieved titles and abstracts were screened according to the following systematic manner. The title of the manuscript was first to be screened, then the abstract, and finally the results within the manuscript. Studies that were given priority were case studies, which involved participants in an attachment analysis survey or other randomized controlled trial. Studies were excluded if the contents of the study did not focus on identifying the characteristics of the avoidant style, or were a record of second-hand accounts.

For the neurobiology part, the terminology themselves were used as search words for literature research.

.png)

Figure 1. Prisma flowchart of research methodology

III. Avoidant Attachment

A. The Origins of Avoidant Attachment

The origins of avoidant attachment are seen to occur in childhood and adolescence, between the avoidant and his or her primary caregivers. Depending on the emotional and physical response from the caretaker, it was seen that the child formed subconscious survival strategies. In a science experiment conducted by Ainsworth, where the reactions of an infant were observed after reuniting with a caretaker after a prolonged period of time, three major responses were observed: 1) contact maintaining, 2) proximity seeking, and 3) proximity avoiding [2]. A follow-up social experiment done by Main & Solomon in 1986 proposed another classification idea, a D group, which had both the tendencies of the A and C groups [6].

The groups A, B, C, and D can be classified in the present era as avoidant, secure, anxious, and disorganized (fearful) avoidant, respectively. While the roots of this study are in infants, the phenomena that caused the infants to respond as they did can be seen to continue during their childhood and adolescent years, thus cementing a particular response pattern in response to different stimuli. This development will often appear in the form of steady affection or maladaptive responses to protect oneself from perceived threats, depending on how the individual interacted with the closest family members as he or she grew up. For example, children of divorced parents are themselves known to have a high divorce rate [7]. This is because the child of the divorced parents did not know what secure affection is, and thus, has a non-realistic or even warped perception of healthy relationships. This is most apparent in avoidant individuals who have an image of an ideal relationship that is quite lofty and has to be “perfect” in order not to trigger the avoidant’s subconscious defense mechanisms.

B. Characteristics of Avoidant Attachment

Although this manuscript primarily focuses on the avoidant attachment style and the disorganised avoidant style, it will also introduce the anxious attachment style in order to contrast how different the anxious attachment style is compared to the two avoidant attachment styles.

The anxious attachment style is often characterized as either “not being enough” or “being too much” in a romantic relationship [8,9]. A healthy and secure relationship often is a partnership of interdependence. However, an anxious individual, for fear of being left behind, from an experience of an abandonment trauma wound, will often try to overcompensate and show unhealthy degrees of codependence. Copendence is often characterized as having an overdependence on one’s love interest, and the anxious individual is often seen to sacrifice his or her autonomy in the romantic relationship [10]. Although the characteristics of an anxious individual are the polar opposite of an avoidant individual, it is these tendencies that initially attract an avoidant individual. Because the avoidants often have a difficult time displaying their emotions, it can be seen that the anxious partner displays the emotions for both parties, until the avoidant individual gets overwhelmed, and initiates a sudden discard or a slow fade away. The lack of closure from the avoidant during the discard often leaves the person who was broken up with in shock and confusion. Indeed, the avoidant can often be seen as copying the very person who caused him or her to display such tendencies in the first place.

As mentioned before, the avoidant is classified as either avoidant or disorganized avoidant. To prevent further confusion, the avoidant individual will henceforth be referred to as dismissive avoidant to prevent confusion with the disorganized avoidant and to illuminate some of the apathetic actions they subconsciously conduct under duress. Regardless of their sub-characterization, certain common patterns appear in the relationships with avoidants.

First and foremost is the tendency to self-sabotage healthy relationships [11]. While the reasons for this self-sabotage are different, it does occur when the relationship starts to enter a serious stage, and thus terrifies the avoidant for different reasons. Second is the continuous tendency to move the goalposts in regard to their partner. Avoidants subconsciously test their partner, and if the partner passes the avoidant’s internal tests, the avoidant will proceed to increase the difficulty until the partner fails their test [12]. This maladaptive strategy is part of a greater need to deflect blame and prevent self-accountability by finding faults in their partner. The goal of this strategy is to build up an argument for why the relationship was doomed to fail from the beginning. Finally, avoidants are objectively horrible at communication, having not been taught how to properly address difficult issues or express their wants and needs [13]. They see frankness as strength and fail to properly identify how their message affects the recipient.

C. Dismissive Avoidant

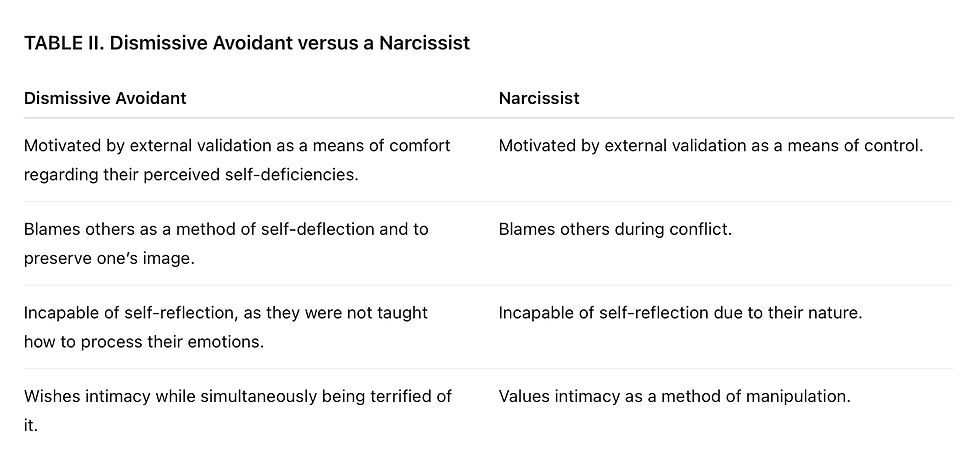

Dismissive avoidants are individuals who primarily fear losing their independence in a romantic relationship. These individuals often see others who display emotions as being too needy or non-disciplined. Other characteristics of a dismissive avoidant include their hyper independence and an inflated view of their self-worth [14]. These characteristics are often the same tendencies seen in narcissistic individuals; they have different reasons why they appear in both the dismissive avoidants and narcissists [15, 16].

While narcissists' primary motivation for their actions is rooted in their thirst for external admiration and control over others, dismissive avoidants display the same tendencies to protect themselves from others. A core wound of shame of the dismissive avoidant of shame and vulnerability. The inflated self-value that a dismissive avoidant places upon themselves is often a mask for their inner fears and insecurities. More often than not, this mask is a result of being around caretakers who were not emotionally available during the dismissive avoidant’s younger years. Every action or response was met with suppressed responses.

For example, if the child expressed sadness or anger, he or she was told to adopt a stiff upper lip. If the child expressed delight or happiness, the response would be lukewarm at best or trodden down upon at the worst. As a result of such interactions, the child will adopt a subconscious belief that displaying emotions rarely gives good results, and thus will start to train a maladaptive process of suppressing their own needs and wants. This lack of healthy emotional processing is often why dismissive avoidants deem individuals who show emotions as too much, while also simultaneously envying them. This envy will eventually become self-loathing as the relationship becomes longer, and the dismissive avoidant will often become overwhelmed by their own emotions and display the four responses often seen in the presence of an external threat: flight, freeze, fawn, and fight.

D. Disorganized Avoidant

In contrast to the dismissive avoidant, the disorganized avoidant displays both anxious attachment tendencies and avoidant tendencies. Depending on the severity of the two, the disorganized avoidant is further divided into disorganized avoidant leaning dismissive or disorganized avoidant leaning anxious. However, it is more intuitive to treat disorganized avoidants as being on a spectrum that goes from anxious to avoidant. What is displayed is often a reflection of the situation.

The disorganized avoidant is an individual who fears being abandoned or betrayed (anxious attachment tendencies) while simultaneously being feared of losing their autonomy, being controlled, and ultimately, making the wrong choice in regards to the significant other [17]. When their anxious triggers are being activated (the abandonment or betrayal wound), they tend to over-compensate or fawn over their partner. However, such overcompensation is not only unsustainable in the long wrong, but will also ultimately manifest in the form of resentment in the avoidant individual.

In regard to communication, or more specifically, the lack thereof, because the disorganized avoidant has been met with emotional neglect when they expressed their justified wants and needs, their communication tends to be incredibly oblique. More tragic is the fact that the disorganized avoidant tends to believe that they are communicating in a proper manner, and starts to resent their partner when the partner is oblivious to their words. Such interactions eventually become a tally on the chalkboard where the disorganized avoidant collects the faults of their partners.

An interesting aspect of the subconscious mind of the disorganized avoidant is the fear of making the wrong choice in regards to romantic partners. Because disorganized avoidants tend to have traumatic backgrounds, where they were abused or outright abandoned by their primary caregiver, an individual they trusted completely, this fear of betrayal appears as a self-fulfilling prophecy in the disorganized avoidant’s mind, as they seek reasons to justify why relationships will ultimately fail. To justify the upcoming “betrayal,” some avoidants distort or suppress their past history. This cognitive re-evaluation is seen in people with past trauma, as the brain and the nervous system try to rewrite history to protect and preserve the self [18].

IV. Avoidant Neurobiology

Compared to the number of psychological studies, the number of studies regarding attachment styles is tragically few in number. This may arise from the fact that it is hard to obtain volunteers who will undergo an MRI exam. If the case study is an avoidant, there is a two-fold fundamental barrier in the fact that most avoidants do not even know they are avoidant, and even if they do know, they will resist and avoid an experiment that exposes their vulnerability [19]. This internal resistance is a sharp contrast to anxious individuals who try to understand themselves with much more assertiveness.

While it is enticing to jump straight into the analysis of how the brain chemistry and structure are affected and different in avoidant individuals, it is imperative to identify the psychological processes that brought about such a difference.

A. Biochemical Interactions

The interactions between a child or adolescent and their primary caregiver are the defining factor regarding the manifestation of avoidant tendencies. The caretaking process is especially important in mammals, as the social interactions help form the basis of the neural network of a young mammal [20].

The initial identification and attachment of an infant to a primary caretaker occur during the stages when the infant’s brain is still being developed. Once the infant has classified who the primary caregiver is, the infant tends to naturally gravitate toward the caretaker in situations of distress and danger. Lack of safe interaction in these situations gives rise to an insecure attachment style which persists into adolescence and adulthood, unless they are treated accordingly [21, 22]. As such, social allostasis, a phenomenon where external regulation, or lack of, by a primary caretaker occurs. In social allostasis, this external regulation is in charge of the internal regulation that occurs within the infant or child.

Recently, Izaki et al. proposed a cascade of events which led to certain neurobiological patterns becoming engraved in one's nervous system [23]. This cascade is made out of four stages: 1) Attachment behavior initiation, 2) Facilitation of caretaker proximity searching, 3) Reunion and alleviation of stress, and 4) Termination of behavior.

They state that multiple portions of the brain and nervous system work together to bring about a specific response. In general, the thalamus sends sensory information to the amygdala, which in turn sends the information to the hypothalamus. This pathway includes the activation of norepinephrine release from the locus coeruleus, dopamine from the basal ganglia to the ventral tegmental area (VTA), and the release of norepinephrine, dopamine, and oxytocin into the hypothalamus [24,25]. The VTA and hypothalamus are of importance as they participate in decision making and social memory retrieval.

The importance of oxytocin in this cascade cycle cannot be emphasized enough. Although it seems that dopamine is critical as it participates in the decision making stage, it is oxytocin which finalizes the response the individual has to a certain situation. Oxytocin and the hypothalamus is in charge of social memory retention, and thus, will help reinforce the positive or negative correlations an individual has with a certain memory, which is, in this case, the reaction of the caretaker. From a biochemical perspective, oxytocin from the hypothalamus decreases the concentration of both cortisol and dopamine, and consequently lowers the urge for fight-or-flight responses. Additionally, in the future, oxytocin is capable of stimulating both dopamine and serotonin, and thus soothes the nervous system [23]. It can be argued that a lack of oxytocin from a deactivated hypothalamus may be one of the core reasons that avoidants have a different stress-response mechanism.

B. Brain Chemistry and Structure

The human brain is a complex computer which compartmentalizes its various specialities in different locations of the brain. Depending on the state of that particular location, different individuals will have vastly different results in the social interactions. Below is a table which indicates the various portions of the brain that showed different responses to certain stimuli or different volumes in individuals.

In this section, the paper will strive to correlate certain parts of the brain and their effect on avoidant individuals. The amygdala participates in threat analysis of the body and is activated in possible threat scenarios. In the case of an individual with avoidant attachment, the amygdala may activate in instances where there is no apparent threat. What is happening is that the amygdala draws upon its past memories and falsely analyzes a situation as a threat. However, the very process of drawing upon past memories is flawed. Because the hippocampus, which is in charge of memory retention and indexing, shows a smaller grey matter volume compared to secure individuals, the avoidant individual may perceive a situation negatively when, in truth, nothing is wrong [30]. It is worth noting that the hippocampus also helps in encoding memories of infants and thus does subconsciously affect the attachment style. [31].

Another result worth noting is the cingulate cortex activation. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and midcingulate cortex (MCC) both participate in decision making, with the ACC specialized in risk management and MCC in cognitive control and challenge response [32, 33]. The activation of the ACC in negative social interaction, or a conflict scenario, and the subsequent activation of the MCC show that an avoidant individual feels that any emotional conflict, even imaginary, will bring about negative consequences. A similar explanation can be given for changes that are recorded in the prefrontal lobe and superior parietal lobule.

Finally, the lack of activation in the striatum, located in the basal ganglia, is part of the reward system. The deactivation of the striatum in response to positive social feedback indicates that social rewards are processed indifferently in the mind of an avoidant [28]. To summarize, the brain chemistry and structure of an avoidant tends to become abnormally tense in scenarios which involve emotional conflict or negative emotional scenarios, while also minimizing and downplaying any possible social interactions.

V. Conclusion

A. Limitations

As mentioned throughout the manuscript, procurement of data and case studies is a struggle in regards to avoidant attachment. In the case where sufficient neurobiological differences are found, the number of patients and volunteers is not very large. Even in the psychological field, the number of avoidant patients who seek therapy is quite smaller compared to the number of individuals with anxious attachment. This is ultimately because of the avoidant individual’s tendency to focus their emotional issues on others. Because avoidant individuals have a deep belief that self-accountability leads to their core fear of defectiveness and vulnerability, they adapt maladaptive responses which are chosen to shift the blame to their romantic partner. Even when people around them suggest therapy or emotional regulation, it is usually after a breakup, and thus, the avoidant has a logical excuse to not entertain the idea of therapy.

Additional research may try to identify the differences between anxious and avoidant individuals in their brain chemistry. A side-by-side investigation in the same portions of the brain using MRI will help paint a more complete picture in understanding the brain usage of the two different attachment styles. A different study might entertain the difference in male and female avoidants, as it was briefly touched upon by Zhang that male and female avoidants utilized different portions of their brains [29]. Such a study can help therapists use appropriate therapy techniques.

B. Healing from Avoidant Attachment

As can be seen in its name, desvenlafaxine is related to venlafaxine. More specifically, desvenlafaxine is an active metabolite of venlafaxine. An active metabolite is a metabolite that itself acts as a drug. As such, desvenlafaxine can be seen as a drug that “skipped a step”. Because it is a metabolite of venlafaxine, it has a similar double-ring structure. Additionally, its affinity toward serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition is similar to duloxetine, in that the affinity to serotonin reuptake inhibition is 10 times greater than that to norepinephrine reuptake inhibition.

Like venlafaxine, desvenlafaxine also interacts with the P-450 enzyme pathway, but only partially. As a result of this partial interaction, approximately 50% of desvenlafaxine is seen leaving the biological system as urine. A biochemical analysis of desvenlafaxine inside urine samples has shown that desvenlafaxine leaves the system without additional biochemical modification, suggesting that desvenlafaxine’s interaction with the P-450 pathway is minimal. Additionally, the metabolite procedure during desvenlafaxine’s limited interaction with the P-450 pathway is not significant.

Daily desvenlafaxine usage ranges from 25-50 mg (Michelson et al., 2001). However, optimal dosage seems to be at 50 mg (Roh et al., 2022). The patient should see results starting from week one, and stabilization should occur near week two (Katzman et al., 2017). The drug kinetics of desvenlafaxine are linear (Sproule et al., 2008).

Acknowledgment

A heartfelt thank you to the anonymous individuals who shared their avoidant stories using various means. Although the first-hand accounts could be utilized in this manuscript, they helped elucidate and lend credence to the subject.

REFERENCES

-

[1] Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Hogarth P.; Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

-

[2] Ainsworth, M. D., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49–67.

-

[3] Murray, C. V., Jacobs, J. I., Rock, A. J., & Clark, G. I. (2021). Attachment style, thought suppression, self-compassion and depression: Testing a serial mediation model. PloS One, 16(1), e0245056.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245056 -

[4] Uccula, A., Mercante, B., Barone, L., & Enrico, P. (2022). Adult Avoidant Attachment, Attention Bias, and Emotional Regulation Patterns: An Eye-Tracking Study. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 13(1), 11.

https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13010011 -

[5] Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226.

-

[6] Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. B. Brazelton & M. W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective Development in Infancy (pp. 95–124). Ablex Publishing

-

[7] D'Onofrio, B., & Emery, R. (2019). Parental divorce or separation and children's mental health. World Psychiatry : Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 18(1), 100–101.

https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20590 -

[8] Sagone, E., Commodari, E., Indiana, M. L., & La Rosa, V. L. (2023). Exploring the Association between Attachment Style, Psychological Well-Being, and Relationship Status in Young Adults and Adults-A Cross-Sectional Study. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(3), 525–539.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe13030040 -

[9] Simpson, J. A., & Steven Rholes, W. (2017). Adult Attachment, Stress, and Romantic Relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 19–24.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.006 -

[10] Claudia, V. (2020). Co-Dependency in Intimate Relationship-A Learned Behaviour. International Journal of Theology, Philosophy and Science. https://doi.org/10.26520/IJTPS.2020.4.6.82-89

-

[11] Peel, R., Caltabiano, N., Buckby, B., & McBain, K. (2019). Defining Romantic Self-Sabotage: A Thematic Analysis of Interviews With Practising Psychologists. Journal of Relationships Research, 10, e16. doi:10.1017/jrr.2019.7

-

[12] Gauvin, S. E. M., Maxwell, J. A., Impett, E. A., & MacDonald, G. (2024). Love Lost in Translation: Avoidant Individuals Inaccurately Perceive Their Partners’ Positive Emotions During Love Conversations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 0(0).

https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672241258391 -

[13] Sessa, I., D'Errico, F., Poggi, I., & Leone, G. (2020). Attachment Styles and Communication of Displeasing Truths. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01065

-

[14] Carvallo, M., & Gabriel, S. (2006). No man is an island: the need to belong and dismissing avoidant attachment style. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(5), 697–709.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205285451 -

[15] Simonsen, S., & Euler, S. (2025). Chapter 21. Avoidant and Narcissistic Personality Disorders. Handbook of Mentalizing in Mental Health Practice, 351–367.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615379019.lg21 -

[16] Podsiadłowski, W., Marchlewska, M., Rogoza, M., Molenda, Z., & Cichocka, A. (2025). Avoidance coping explains the link between narcissism and counternormative tendencies. British Journal of Social Psychology, 64, e12816.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12816 -

[17] Beeney, J. E., Wright, A. G. C., Stepp, S. D., Hallquist, M. N., Lazarus, S. A., Beeney, J. R. S., Scott, L. N., & Pilkonis, P. A. (2017). Disorganized attachment and personality functioning in adults: A latent class analysis. Personality Disorders, 8(3), 206–216.

https://doi.org/10.1037/per0000184 -

[18] Mary, A., Dayan, J., Leone, G., Postel, C., Fraisse, F., Malle, C., Vallée, T., Klein-Peschanski, C., Viader, F., de la Sayette, V., Peschanski, D., Eustache, F., & Gagnepain, P. (2020). Resilience after trauma: The role of memory suppression. Science (New York, N.Y.), 367(6479), eaay8477. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aay8477

-

[19] Torrico TJ, Sapra A. Avoidant Personality Disorder. [Updated 2024 Feb 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559325/ -

[20] Callaghan, B. L., & Tottenham, N. (2016). The Neuro-Environmental Loop of Plasticity: A Cross-Species Analysis of Parental Effects on Emotion Circuitry Development Following Typical and Adverse Caregiving. Neuropsychopharmacology : Official Publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 163–176.

https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.204 -

[21] Fraley, R. C., Roisman, G. I., Booth-LaForce, C., Owen, M. T., & Holland, A. S. (2013). Interpersonal and genetic origins of adult attachment styles: a longitudinal study from infancy to early adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(5), 817–838.

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031435 -

[22] Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: four lessons. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008

-

[23] Izaki, A., Verbeke, W. J. M. I., Vrticka, P., & Ein-Dor, T. (2024). A narrative on the neurobiological roots of attachment-system functioning. Communications Psychology, 2(1), 96.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-024-00147-9 -

[24] Goel M, Mittal A, Jain VR, et al. Integrative Functions of the Hypothalamus: Linking Cognition, Emotion and Physiology for Well-being and Adaptability. Annals of Neurosciences. 2024;32(2):128-142. doi:10.1177/09727531241255492

-

[25] Hou, G., Hao, M., Duan, J., & Han, M. H. (2024). The Formation and Function of the VTA Dopamine System. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 25(7), 3875.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25073875 -

[26] Vrtička, P., Bondolfi, G., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2012). The neural substrates of social emotion perception and regulation are modulated by adult attachment style. Social Neuroscience, 7(5), 473–493.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2011.647410 -

[27] Schneider-Hassloff, H., Straube, B., Nuscheler, B., Wemken, G., & Kircher, T. (2015). Adult attachment style modulates neural responses in a mentalizing task. Neuroscience, 303, 462–473.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.06.062 -

[28] Vrticka, P., Andersson, F., Grandjean, D., Sander, D., & Vuilleumier, P. (2008). Individual attachment style modulates human amygdala and striatum activation during social appraisal. PloS One, 3(8), e2868.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0002868 -

[29] Quirin, M., Gillath, O., Pruessner, J. C., & Eggert, L. D. (2010). Adult attachment insecurity and hippocampal cell density. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 5(1), 39–47.

https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsp042 -

[30] Zhang, X., Deng, M., Ran, G., Tang, Q., Xu, W., Ma, Y., & Chen, X. (2018). Brain correlates of adult attachment style: A voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Research, 1699, 34–43.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2018.06.035 -

[31] Yates, T. S., Fel, J., Choi, D., Trach, J. E., Behm, L., Ellis, C. T., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2025). Hippocampal encoding of memories in human infants. Science (New York, N.Y.), 387(6740), 1316–1320.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adt7570 -

[32] Holec, V., Pirot, H. L., & Euston, D. R. (2014). Not all effort is equal: the role of the anterior cingulate cortex in different forms of effort-reward decisions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 12.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00012 -

[33] Shackman, A. J., Salomons, T. V., Slagter, H. A., Fox, A. S., Winter, J. J., & Davidson, R. J. (2011). The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 12(3), 154–167.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2994 -

[34] Whitaker R. C. (2016). Relationships Heal. The Permanente Journal, 20(1), 91–94.

https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/15-111